Why Are Spices So Flavorful?

A Sensory Journey through History, Chemistry, and Evolution

LAST UPDATED: August 25, 2025

READ TIME: 10 minutes

Table of Contents

Food Perfume

Long before salt and sugar became staples, before refrigeration or pasteurization, the culinary world already had its greatest magicians—spices and herbs. In ancient Hindustan, the Spice Islands, and the ports of Arabia, their provocative aromas twisted through bazaars and trade routes, changing the course of history.

For our ancestors, spices weren’t simply the indulgences of a cook. They preserved food, masked unpleasant odors, and helped prevent illness—uses that were all discovered and honed centuries before microbiology.

Today, we reach for spices and herbs mostly for their flavor, but that flavor is the direct result of an evolutionary arms race. Spices and herbs are plants’ chemical weapons, and the reason they smell and taste so intoxicating to us lies in the biology, chemistry, and survival strategies of the plants themselves.

The Chemistry of Flavor

Primary vs. Secondary Compounds

Every plant runs on what's called "primary metabolism," the processes that keep it alive: photosynthesis, nutrient uptake, and growth. But many plants also produce secondary compounds, chemicals that aren’t strictly for survival in the short term, but offer huge advantages in the long term.

These secondary compounds are the source of spice and herb flavors. They evolved mainly as defenses: to repel insects, deter grazing animals, and resist fungi and bacteria. We often call them "flavor and aroma compounds," or "flavor molecules." You can learn more about the compounds that contribute to each spice and herb's flavor profile under the "Chemical Composition" section in each spice or herb profile.

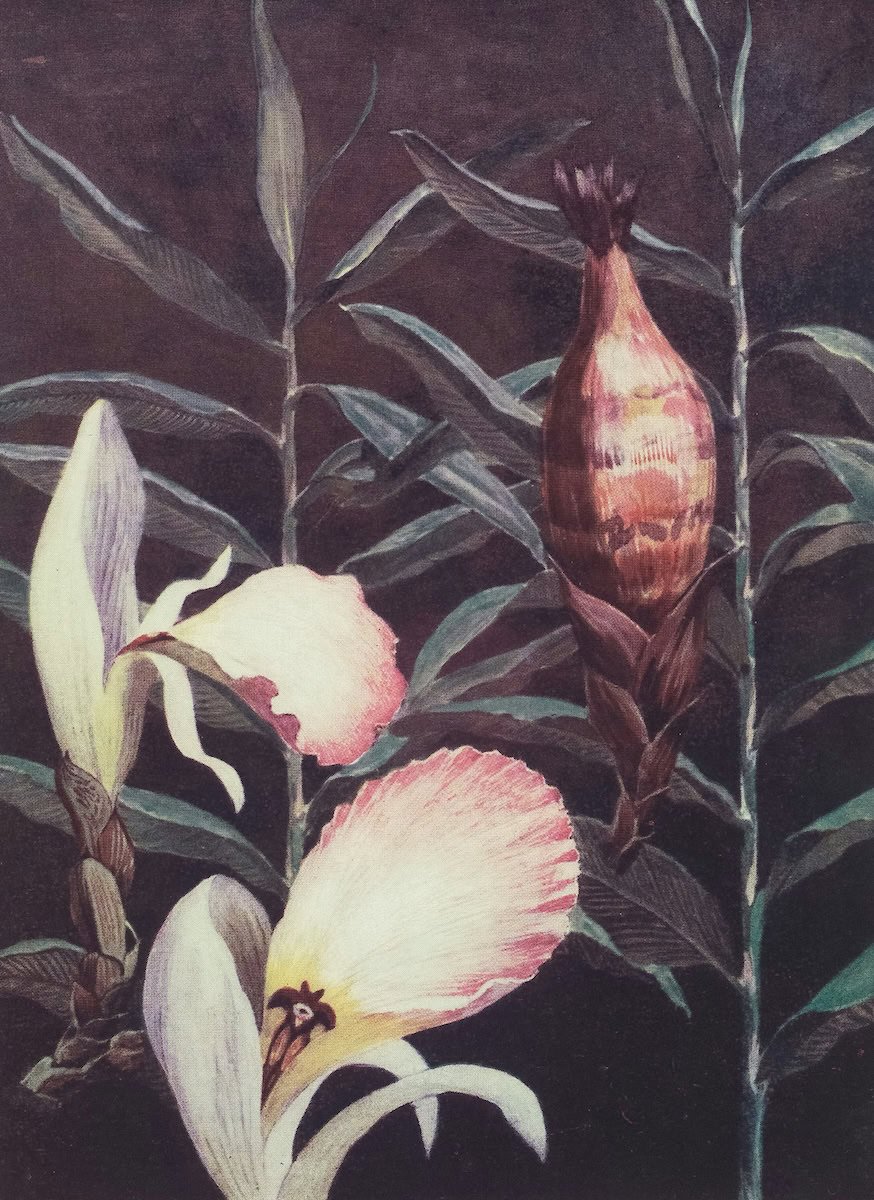

Aroma Bubbles

Most flavor molecules in spices and herbs are oil-soluble. In the living plant, they’re stored away in glands or ducts. You can often see them as tiny bubbles (pictured below). They remain sealed off until the plant is damaged, but when an insect chews on a makrut lime leaf, for instance, the glands rupture. Oils spill out, volatilize, and release a burst of aroma into the air. From the plant’s perspective, it's a distress signal, and an effective one at that. That bug will not be taking another bite.

The same aroma is released when a cook bruises or tears one of these leaves. Every time we chop, grind, grate, temper, and crush spices and herbs, we are intentionally triggering the plant's defense mechanisms. We do so because the same chemicals that taste foul or even deadly to a caterpillar are beautifully aromatic, stimulating, and delicious to us. Why is that?

Why Plants Make Flavor

Defense Against the Smallest Enemies

While thorns and bark fend off large herbivores, most plants’ true enemies are microscopic. Bacteria, fungi, and molds—the decomposers—can destroy leaves, fruit, and seeds much faster than any grazing animal.

In tropical climates, plants face an even greater challenge, as heat and humidity accelerate the growth of microbes. Luckily, natural selection is great at building chemical defenses, and chemical defenses are often elegant solutions.

Grains of paradise arm themselves with paradols and gingerols—fiery cousins of the compounds in ginger—that are so potent, they’re even effective against drug-resistant strains of fungi. Oregano's thymol and carvacrol fight the good fight against mold and can punch holes in bacterial cell walls. Allicin in garlic is so broadly antimicrobial that it can even inhibit some viruses. Mustard seed, wasabi, horseradish, and nasturtium release isothiocyanates, sharp compounds so irritating that they act like chemical tear gas against microbes and pests.

But not only do spices defend, they also camouflage themselves. Unripe black pepper fruits are green, blending seamlessly with the surrounding foliage. They literally hide in plain sight until they’re chemically armed with enough piperine to protect the pepper plant. They then turn bright red, beckoning birds to help spread the seeds.

Natural Attraction

Capsaicin in chiles works the same way. It deters most mammals, but doesn’t bother birds.

Birds lack the receptor (TRPV1) that mammals have for sensing capsaicin and piperine. They simply don’t feel the heat. For the plant, this is perfect: microbes, insects, and mammals are discouraged from eating them, while birds are encouraged to. The seeds pass through their gut fully intact, so they’re perfectly suited to disperse them.

In fact, the relationship can be even more symbiotic. For allspice, which also turns bright red when mature, passing through a bird’s digestive tract is sometimes even necessary for its seeds to germinate!

So spices are not just repellents; they can also attract. Clove’s eugenol draws in beneficial insects while repelling detrimental ones. The sweet scent of basil can lure bees. And humans, too big to be killed by these chemicals, fell in love with them. Not only do they attract pollinators, but also us!

Why We Like “Poison”

But we must keep in mind that to most organisms, spices are poisonous. We're not big enough to stay safe from their poison in high enough doses. Many spice compounds can be toxic in excess. Nutmeg abuse can damage the liver and make you hallucinate. Too much capsaicin can cause tissue damage.

We are unusual among animals in not just tolerating these chemicals but actively seeking them out. In the small amounts used in cooking, these same compounds breathe much-needed life into food and help us defend our bodies:

- Their antioxidant action helps protect us against oxidative stress.

- Their anti-inflammatory effects help us heal and prevent chronic conditions.

- Many spices also boost our immune system!

When you think about it, if spices were "designed," so to speak, to kill microbes, and these are the same microbes we don't want in our food, then we share a common enemy!

How's that for symbiosis? We get better-tasting, better-preserved food that makes us healthier. Spice and herb plants get increased propagation and almost guaranteed survival (at least while we’re still around). It is an ancient, sacred partnership.

Evolutionary Taste

The Darwinian Gastronomy Hypothesis

Building on this concept, some scientists suggest our enjoyment of spices was selected for over time because spice-eaters were healthier than non-spice-eaters in environments where food itself is one of the greatest dangers. Put simply, we evolved to enjoy spice and herb flavors because they kept our food safe. In hot climates without refrigeration, food spoils quickly.

Recipes from tropical regions, such as India or Thailand, often call for a dozen or more spices per dish—many with strong antimicrobial properties. The reason is two-fold. As long as they have complementary flavor profiles, the more the merrier with spices and herbs. Complexity with flavor is like an orchestra versus a solo. Both are great. You can still immensely enjoy a slice of peach dusted with freshly ground mace only. But it's hard to argue against a symphony. When you have so many flavor compounds working together, the results are literally awe-some.

Complex blends like curry powders and garam masalas are delicious, yes, but they also may have been developed partly because their combined antimicrobial range was broader than any single spice alone. Some combinations are greater than the sum of their parts. For instance, lemon juice can amplify the antibacterial effect of garlic or black pepper by lowering pH and weakening bacterial defenses.

In favor of the "Darwinian Gastronomy" hypothesis, comparative studies show that:

- Hotter countries use more spices. India’s average recipe may use 9+ different spices; Norway’s, fewer than 2.

- The most-used spices in the hottest climates are also the most antimicrobial, like cloves, cinnamon, oregano, and garlic.

- Regional culinary differences mirror climate. Southern Chinese recipes use more spices, and more potent ones, than northern dishes.

Arguing over whether or not this theory is entirely accurate from an evolutionary perspective misses the point. The logic is simple: in environments where bacteria thrive, people who used spices were less likely to get sick. Keep in mind, this is before the age of refrigeration. In colder climates, far away from the equator, food didn't spoil as quickly because the environment itself offered a form of refrigeration—the lower temperatures naturally slowed the proliferation of microbes. Those are the very places where fewer spices evolved in the wild, and where people didn't need to rely on them as much to preserve their food.

This is also true of a region's cuisine. Take Japan, for example. Surrounded by the sea on all sides, fish were the most abundant food source. Wasabi, native to Japan, was the perfect complement. Its infamous heat is also intensely antimicrobial, so eating it alongside raw fish dramatically reduces the risk of foodborne illness. The cuisine's most iconic spice, then, is not only essential for its flavor, but also for making the food itself less dangerous to eat.

Over generations, this Darwinian preference for safe food became cultural tradition. Once a culture embraces the use of spice, the preference is taught early. Children in tropical cultures often develop a taste for heat or bitterness at a young age. In cooler climates, most spices are acquired tastes.

So now we know why plants create flavor (their armor and artillery) and why we enjoy it. But how do we perceive it?

The Nature of Flavor

Taste and flavor aren’t the same thing. Taste is limited to five categories that the taste buds on our tongues can detect: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. Flavor is taste plus aroma plus mouthfeel (like the cooling of mint, the heat of chili, and the crunchy texture of toasted whole seeds).

Our noses carry the heavy lifting. About 80% of what we perceive as flavor is actually aroma, while only ~20% comes from taste. Humans have 400 types of odor receptors capable of detecting over a trillion scent combinations. A spoonful of curry delivers sweetness, salt, and heat to your tongue, but its complexity comes from hundreds of aromatic molecules rising into your nasal passages.

This is one of the reasons why we breathe in through the nose as we draw in a succulent bite. Increased aroma perception enhances flavor. The key distinction is that we can experience aroma on its own by smelling something and not eating it, while we rarely experience flavor without aroma (taste only). This only happens to a degree if you plug your nose intentionally to eat something unpleasant, which works well because ~80% of the unpleasantness is now gone. Conversely, serious nasal congestion sadly makes food much less tasty during an allergy attack or a cold—the flavor is there, you just can't perceive it.

You can play with this concept for fun. Simply pinch your nose while sipping cinnamon tea, and it will taste only vaguely sweet. Release your nose, and suddenly the cinnamon “appears.”

Here are some other ways to think about the nature of flavor:

The Music of Flavor

Flavor terms borrow from music. Aromas have top notes—the bright, fleeting molecules that hit your nose first (like the linalool in fresh basil), middle notes that form the body of the aroma (vanillin in vanilla), and base notes that linger the longest (eugenol in cloves).

Drying herbs often strips away top notes, which is why dried basil smells nothing like fresh. Grinding spices releases all notes at once, which can be great for a dish if you just ground them prior to cooking. But because volatile compounds evaporate extremely quickly, pre-ground powders lack much of that spice's complexity as the most desirable top notes have dissipated.

The Language of Flavor

Flavor chemistry helps explain why certain pairings “work.” Two ingredients that share key aroma molecules often taste harmonious, like jasmine and pork with indole or cloves and banana with eugenol. They speak the same flavor language, and our taste buds and noses can understand it.

As you add more spices and herbs that speak the same language to a dish, the sensory experience becomes much richer. As we mentioned earlier, this is why spice blends have endured for centuries—they give food depth and intrigue.

The DNA of Flavor

Another useful analogy is DNA. We share much of our genetic code with chimpanzees because they're our closest living relatives. Likewise, two spices with similar chemical makeups, even if they’re not very related botanically, are like culinary cousins. Chemical composition is the DNA of flavor.

Borrowing Armor

Spices and herbs are, in essence, plants’ evolutionary armor; their chemical quills and shells. We’ve turned these defensive compounds into cooking treasures, using them not just to keep food safe but to delight our senses.

Every time you crush coriander, shave nutmeg, grate ginger, or tear fresh mint, you’re triggering the same chemical defenses that help keep those plants alive. The next time you season a dish, take a moment to breathe in deeply. Behind that aroma lies a story of survival, and the extraordinary partnership between plants and people.